Military Schools Project Supports Peer Learning Program

January 09, 2013 / by Linda Jackson- Research

When one child teaches a skill or concept to another child, the experience benefits both of them.

That’s the idea behind Learning Together, a peer-teaching intervention funded by the USC School of Social Work’s Building Capacity in Military-Connected Schools project that is being implemented this year with middle school students at San Onofre School on Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton.

Based on a program used in Israel for almost 30 years, Learning Together trains students to tutor struggling students who are two grade levels below them. But instead of being the top achievers in their class, the tutors are typically those who are below proficient and might even exhibit behavior problems in the classroom – those that Assistant Principal Christine Kay described as “frequent flyers” to the office.

“It was OK with us if the students were a little squirrely,” Kay said. “We wanted students who might need some leadership opportunities.”

Both the tutors and their parents, however, showed some initial skepticism over the teachers’ choices.

“We had some parents say, ‘Are you sure you want my child?’” Kay said.

While Learning Together can work in any school, Kay and Principal Julie Hong believe the program is well-suited to military-connected students because it helps them form stronger relationships with their peers, take on responsibility and build a sense of community toward their school—qualities that might not be very strong in students who change schools frequently.

“All kids require attention and want to be noticed,” said Torrey Tice, a reading specialist who led the program last year. But she added that military children respond especially well to being positively recognized.

Creating a stronger community among San Onofre’s middle school students is why Kay and Hong decided to shift the program from the elementary to the middle grades, with 6th through 8th graders tutoring 4th through 6th graders.

“We see a need to provide our middle schoolers a purpose for being here and a buy-in to their education,” Kay said.

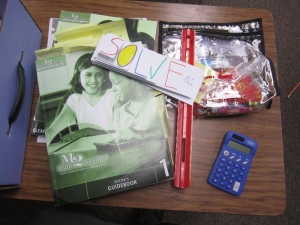

At the beginning of the program, tutors are brought together for a leadership academy, a two-day “conference” in which they are introduced to the program and their responsibilities. Then on a weekly or twice-weekly basis, the teacher leading the sessions brings the tutors together for a lesson that they in turn teach to their tutees the next day.

The lessons include a story, some history and a math problem related to the topic. Tutors stick to a script that explicitly tells them what to say to their tutees and what to do at each point during the session. Teaching the lessons builds and reinforces the skills that the tutors might be lacking, as well as develops their organizational skills.

“It really makes students slow down and break down the problem,” Tice said. So if a student has fallen behind because he or she doesn’t always read instructions or tries to rush through a problem, this teaching process forces them to practice following the steps needed to solve it.

Tutors are also led through debriefing sessions to discuss how their lessons went and what they could improve on during the next lesson.

Last year, San Onofre piloted a month-long version of the Learning Together program, which allowed organizers to work out some of the logistics. They learned that it’s important to have support among the faculty because tutors and tutees miss some class time to participate, and scheduling creates some challenges. In military-connected schools and any schools with high student turnover, Kay and Hong also recommended choosing more tutors than tutees in case a tutor leaves the school during the program.

A preliminary evaluation conducted by the Building Capacity team found that even with the short time frame, there was enough evidence to suggest that the school could implement a longer, expanded program to include more students.

Bill Billingsley, director of special programs for Fallbrook Union Elementary School District, said based on these results, officials plan to expand the program to the other K-8 school on the base Mary Fay Pendleton School, Potter Junior High, and possibly one or more elementary school sites.

“We are dedicated to building capacity within our district and expanding the program to benefit as many district students as possible,” he said.

Because the pilot program was so short, Kay and Hong knew not to expect significant academic growth in any of the students. But they hoped for—and did see —improvements in behavior and relationships with other students. Bonds were formed between tutors and tutees.

“[They] had a model, someone to look up to,” Tice said.

In debriefings following the pilot, one particular student proved to be especially impressive. He was initially told he might lose his position as a tutor because he was disruptive in class and had a hard time paying attention. Faced with the prospect of being replaced, he pledged to improve. Later, in a conversation with Kay, he was able to articulate what he gained from the program.

He told her, “I didn’t think I could actually help someone else.”

To reference the work of our faculty online, we ask that you directly quote their work where possible and attribute it to "FACULTY NAME, a professor in the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work” (LINK: https://dworakpeck.usc.edu)